Uchima Ansei and Uchima Toshiko ExhibitionJuly 17 Tues. - Aug 10 Fri.

2018 11:00-19:00 |

|

After Ansei Uchima, who in the 50s was a member of the Sosaku Hanga Movement led by Koshiro Onchi, and Toshiko Uchima (nee Aohara), a member of DEMOKRATO Art Association led by Q Ei, wed in 1954, they decided start a new life in America to walk their path of art. They moved together with their infant son Anju. This was 60 years ago. In December of 1982, Ansei Uchima collapsed, and after several years living with illness, passed away in May of 2000. Toshiko, who resolutely supported him during that time, joined him that December.

Since then, 18 years have passed.

Today, Toki no Wasuremono has worked

with the support of the Uchimas’

bereaved family in New York to present

the exhibition, “Uchima Ansei and Uchima

Toshiko”.

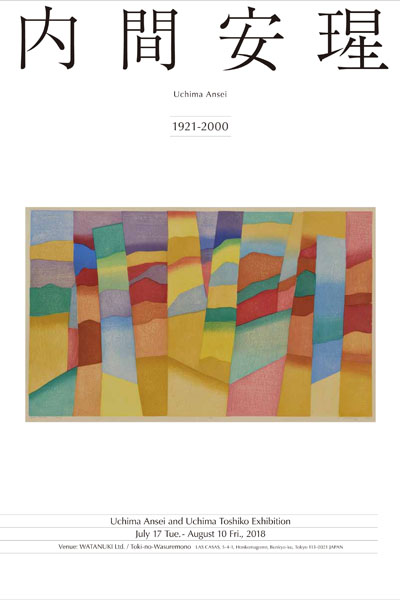

After many years of trial and error,

Ansei intensified the traditional

methods of ukiyoe to develop his own

unique method which he used to create

his “Forest Byobu” series. In this

exhibition we will present vibrant

woodblock prints created between 1957

and 1982 abundant with a modern

sensibility.

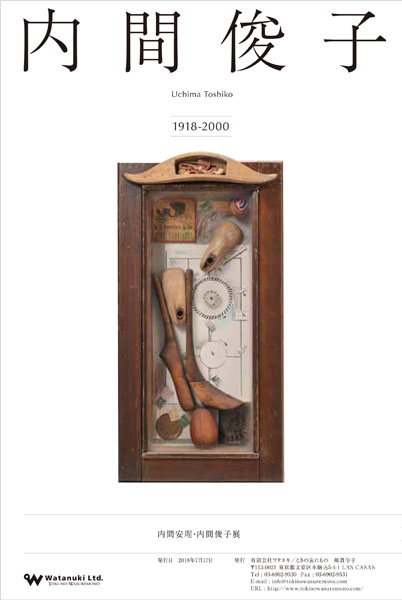

Toshiko was active in the avant-garde from early on, and after crossing to America in 1966, she began to create box-shaped assemblages by sealing old wood and stones, finding success in solo exhibitions across the United States and Japan. Following her husband’s illness in 1982, Toshiko became fully devoted to taking care of him, but still continued to create works in her now limited spare time. With themes like “dreams, hopes, and memories”, the works which are made up of everyday objects express a record of Toshiko’s life.

We have prepared 50 works, but based on the space available for this exhibition, the display is limited to around 20.

My Parents: A Reflection

Anju Uchima, Son

Art Lawyer in New York

In late 1959, my parents, both approaching middle age, left behind what must have been a familiar and comfortable existence in Tokyo to forge a new, uncertain path in the United States. They had achieved a certain amount of recognition as artists in Japan, my father associated with the sosaku hanga movement and my mother with the Demokrato Artists Association. They had just had a child; I was a one-year-old at the time. Almost everybody they knew was in Japan. Starting over in America was a bold and risky move: they had essentially nothing, as my mother often said, but trust in their own character and ability to pursue their dream of succeeding as artists in a new world. They were not assured success in art, or in any other field, for that matter. They did not know where in the States they would settle, much less how they would support themselves.

Though my father was returning to the country of his birth, he had been away for half of his life, so long that he was a bit of an “Urashima Taro.” Through that time, in Japan, he had reached adulthood, lived through the country’s hardest days in the War and its aftermath, chosen his career, made many friendships and started a family. He could certainly have stayed there. For my mother, who knew no country other than Japan, the move required an even deeper faith in the future. The exact reasons for my parents’ decision have never been clear to me; no doubt many factors, including the desire for fresh perspectives and an individualistic spirit, played important roles.

Of my father’s life prior to that point, I know relatively little. I heard, very occasionally, references to my father’s youth in California: he had played American football in high school, earned a black belt in judo and had had the same art teacher in high school as Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston, who had both been, by about ten years, his senior in the same school. I knew a little about his parents, who had immigrated from Okinawa to California in 1920, worked hard in various lines of work including running a store and farming, and done well enough to raise a large family and earn income from some modest real estate holdings in Los Angeles. From what I could gather, the family, which included my father’s two younger brothers, was part of a large Japanese-American community in California with no particular “Okinawan” identity, except that my grandmother played the jamisen. My father never spoke to me about his twenty years in Japan and only rarely about any other details from his past. He was reserved outside of social settings and ordinarily so consumed by the “here and now” of his daily life that he had little time or inclination to share his memories.

My mother, by contrast, spoke often about her past. I know many details about her family and her early life in colonial Manchuria. Her father was a well-to-do businessman and my mother grew up in comfortable surroundings, attending good schools (ultimately Kobe College), filled with art and music lessons. From an early age, she had a passion for art. She always had a strong desire to succeed and, in her own words, hated to lose at anything, qualities that undoubtedly propelled her to become one of the few women to be active in the Japanese art world in the early-to-mid-1950’s. Even before meeting my father, my mother had desired to come to America to further her art career. She had worked as an artist at the library of an American military base in Kobe and become friendly with her superior, a Miss Newenham, who had offered to take my mother back with her to the States upon her return and help her to develop an artistic career there, plans which could ultimately not come to fruition. About my mother’s artistic career in Japan, however, I know little. I do recall her speaking about her experiences with Demokrato but, because the names and details associated with it were too far removed from my day-to-day concerns, they did not stay in my memory.

Leaving Tokyo, my parents arrived in Los Angeles, where my father’s parents and brothers lived. Weeks later, my father, unimpressed with what he saw in local art galleries, decided to leave the only American city in which he had roots and move east, exchanging ideas about where to go with his friends Oliver Statler, who was in Chicago, and Isamu Noguchi, who was based in New York. In the early part of 1960, my parents decided to settle in New York, then as now a cultural capital and a mecca for artists from around the world. My parents found a small, congenial group of Japanese artists living in New York at the time whom they had known in Japan, including Inokuma Gen’ichiro, Izumi Shigeru, Mori Yasu and AY-O. They socialized often and helped one another. Black-and-white photos from those early days show happy moments with the three of us and these friends in Central Park and on the beach at Coney Island. My father began a life characterized by an almost single-minded devotion to his work, which consisted of artistic production and art teaching, first at Pratt Institute and then at Sarah Lawrence College and, later, also in the evenings at Columbia University.

In 1962, we moved from the top floor of a five-story walk-up building in Greenwich Village to a larger building in Upper Manhattan with an elevator, where we lived until 1976. My room and my father’s studio were side-by-side, farthest away from the entrance. Embedded in my memories are the constant repetitive sounds of my father carving his wood blocks with his cutting tools and rubbing his baren onto sheets of Japanese paper; the radio playing the news, talk shows and classical music; and, periodically, my father’s sweeping the carved wood chips that had gathered on the floor. When he was not teaching, he was in his studio all day long. He had no hobbies and his reading material consisted mainly of the newspaper and books to further his understanding of art and his medium, bearing titles like Printmaking; The Book of Fine Prints; Master Prints of Japan; An Introduction to a History of Woodcut; Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin; Painting in the Yamato Style; and Bonnard, among many others. His studio was intensely practical. Nothing was extraneous or placed for aesthetic or sentimental reasons. All of the room’s neatly arranged contents - every tool, tube, jar, bottle, can, brush, piece of charcoal, pencil, ruler, rag, piece of paper, wood, cardboard - had a specific function directly connected to steps in his creative process. For all its proximity to my quarters, the studio was in a different world. I rarely dared disturb my father’s work and ventured inside the room only on occasion when both my parents were out of the apartment. I cannot remember my mother ever entering the room.

During the early years, my mother, for the most part, set aside her artistic career in order to care for me, tend to the housekeeping and create an environment that would support the development of my father’s career. For this reason, I was only dimly aware as a child that my mother was an artist in her own right. She continued her work when she found the time; it was only when I entered middle school and required less attention that my mother began producing work on a regular basis. Though she had been a printmaker in Japan and did some prints in New York, she went on to choose an entirely different medium, perhaps out of a desire to create works completely distinct from my father’s and to create an environment in which my father’s printmaking career could flourish without distraction. Whatever the reason, there is no doubt that her new medium - collage and box assemblage - was uniquely and perfectly suited to her personality and aesthetic sensibilities.

My mother’s creative world was filled with romance and sentiment drawn from memory and imagination. She loved objects and treasured the past. In her youth, she had been nicknamed “o-senchi nesan” for her sentimentality. One of the phrases that gave meaning to her life was “ano toki, ano hito,” referencing her frequent recall of special moments spent with particular people in particular places. She expressed her passion for memory through objects and imagery from the world’s past, filtered through her imagination. Glimpses from the Edo period, the Italian Renaissance, the Victorian era and colonial America; items from bygone eras such as old stamps, postcards, dolls, toys, music scores; her favorite symbols of angels and hearts; natural elements like leaves, seashells, stones, roses and feathers, were arranged with small tools, hand mirrors, magazine clippings and other objects, and projected elegant, fanciful moods. Unlike my father, who discarded unneeded items without a thought, my mother would save objects and search for new ones at antique shops and flea markets, keeping them for inspiration and use in her work. She used a large work table on one side of my parents’ bedroom, with scissors, glue, gold and silver-colored pastels and other implements, and stored her objects in a large file cabinet to the side.

As a couple, my parents socialized frequently with others, both Japanese and American, involved in the fine arts. To Japanese artists, both living in New York and visiting from Japan, my parents were congenial hosts and, over the years, had many of these old friends at our home for dinner parties and visited museums and other places of interest with them in New York. There were too many to remember, but among those I can recall are Yoshida Hodaka, Yoshida Toshi, Yoshida Masaji, Munakata Shiko, Kitaoka Fumio, Nagare Masayuki, Yuki Rei, Hagiwara Hideo, Kado Hiroshi and Takahashi Rikio. To the Americans, my parents were friendly colleagues in New York’s art world and, often, emissaries of Japanese culture, often introducing them to sukiyaki or sashimi over our dinner table and serving as sources of information about Japan and Japanese art. I can remember, among many others, the artists Fritz Eichenberg, Michael Ponce de Leon, Bernard Childs, Seong Moy, Letterio Calapai, Karl Schrag and Richard Pousette-Dart, and art authorities like Una Johnson and Dore Ashton, in addition to colleagues from the art faculties of Sarah Lawrence College and Columbia University.

My parents were also in regular contact with Isamu Noguchi, with whom they had become friendly in Japan, my father having met him sometime in the early 1950s and, I understand, assisted and collaborated with him in various endeavors in Japan. I can remember Noguchi visiting us at home and spending some afternoons with him and my parents at the countryside home of Noguchi’s sister, with whom my parents were also friendly. My father also maintained a lifelong friendship with author Oliver Statler, for whom he had played a key role in Japan, enabling Statler to communicate with the artists featured in his 1956 book Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, and accompanying him to interviews for his 1961 work Japanese Inn. We visited him in Chicago and my father met with him on several occasions in Japan in the 1970’s as well.

As a family, we traveled widely between 1970 and 1975. In 1970, on the occasion of my father’s second Guggenheim Fellowship and a sabbatical from Sarah Lawrence College, we journeyed through Europe and then to Japan, where we spent two months, mainly in Kyoto, before returning to Florence, Italy, where my father taught at a six-week American summer program. Over the summers of the next five years, my father taught at another American summer school in southern France. On those occasions, we covered many destinations in France, including Provence, the Loire Valley, Normandy, Strasbourg, the Riviera and Brittany, and continued on to Italy, Switzerland, Greece and Yugoslavia. We tirelessly toured places of cultural interest, from several dozen temples in Kyoto, the Uffizi and Prado Museums, the ruins of the Parthenon and numerous chateaux and cathedrals, to Biennale exhibitions in Venice and Ljubljana. These experiences provided my parents fresh sources of inspiration and undoubtedly influenced their later works, as did the natural surroundings of my parents’ country house in Shrub Oak, New York, which my parents bought in 1979.

What had started as an uncertain venture for my parents in 1959 blossomed into forty successful years in the United States rewarded in numerous ways. Though my father was never very interested in self-promotion, he achieved significant recognition, with two Guggenheim fellowships and the inclusion of his work in, among other places, the collections of the Metropolitan Museum, the National Gallery, the British Museum, the Rijksmuseum and the Whitney Museum. In teaching, too, his years of dedicated instruction were recognized, first with a grant of tenure and, ultimately, appointment as emeritus faculty at Sarah Lawrence College. My mother, with the iron will and determination that co-existed with her sentimentality, masterfully balanced home and career, creating a distinguished oeuvre of works exhibited in both the United States and Japan, while raising me and providing support for my father, both throughout his career and during the eighteen years following his stroke in 1982.

My mother occasionally wondered how she and my father would have fared if they had not left Japan. I believe they had no regrets. In her last years, my mother said on several occasions that she and my father had lived “an American Dream,” starting with little and achieving, completely on their own terms, two brilliant careers in which they could take pride, raising a child and laying roots in New York for successive generations of family, and making the most of their character and ability, in which they had placed so much faith in starting their lives over in America.

●We will publish

an exhibition catalogue

『Uchima Ansei and Uchima Toshiko

Exhibition』Catalogue

2018

Published by Toki-no-Wasuremono

B5 24pages Images:51 Biography

Text:Anju Uchima(Eldest son, art

lawyer/New York)

Design:Okamoto Issen Design Studio

Edited by:Reiko Odachi

Assistance:Noriko Kuwahara

Translation:Chiaki Ajioka、others

800 yen (incl. tax)※shipping fee of 250

yen

■ Ansei

UCHIMA (1921-2000)

Uchima was born 1921 in Stockton,

California. In 1940, he went to Tokyo to

study architecture at Waseda University.

After the war, Uchima met the sosaku

hanga artist Onchi Koshiro, and began to

venture into abstract woodblock

printing. He held his first solo

exhibition at Yoseido Gallery (Tokyo) in

1955. In 1960, he relocated to New York,

where he received twice a Guggenheim

Fellowship for print artists (1962 and

1970). Uchima taught at Sarah Lawrence

College, and held a position as an

adjunct professor of printmaking at

Columbia University. He died in 2000,

aged 79.

■ Toshiko

UCHIMA (1918-2000)

Born 1918 in Manchuria, Uchima enrolled

as a student at Dalian Institute of

Painting in 1928. In 1939, she completed

her studies at Kobe College. Since she

moved to Japan, she furthermore studied

with the painter Ryohei Koiso. In 1953,

Uchima became a member of the Democratic

Artists Association founded by Q Ei.

Around the same time, she met Sadajiro

Kubo and Shuzo Takiguchi and started to

experiment with abstract oil painting,

woodblock prints and lithographs. In

1955, she became a founding member of

the Japanese Women’s Print Artists

Association. Three years later in 1958,

Uchima participated in the Triennial of

Contemporary Printed Art in Grenchen

(Switzerland), subsequently shifting her

main activities to the United States.

Since 1960, she lived in New York. Since

around 1966, Uchima’s work started to

center on box-like assemblages and

collages made of impressions on wood and

stone. Her works have been exhibited

across the United States and in Japan.

When her husband, fellow print artist

Ansei Uchima, suffered a cerebral

haemorrhage in 1982, she devoted most of

her time over the next 18 years to take

care of him, though she also continued

to be active as an artist. Uchima passed

away in 2000.

<Uchima Ansei and Uchima

Toshiko Exhibition> List of works

July 17 Tues. - Aug 10 Fri. 2018

11:00-19:00

*Click the image to enlarge

.jpg)

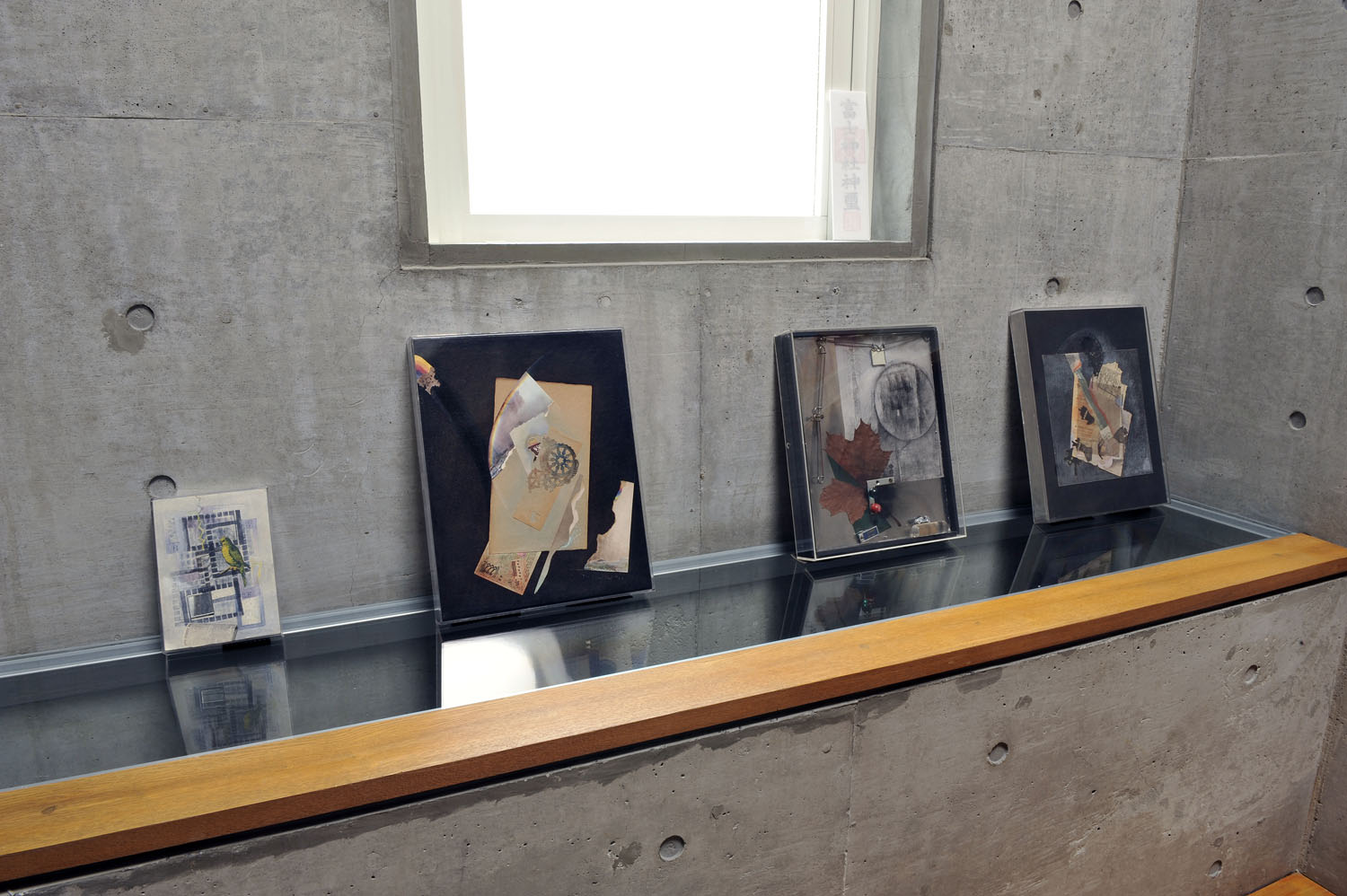

Gallery view

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|