29th Q Ei Exhibition (Web Exhibition)May. 8[Fri.]―May. 30[Sat.] 2020 11:00-19:00 |

Otani Shogo, the Chief Curator of The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, wrote about this exhibition (Web exhibition). The full text is posted below.

To view web exhibition movies, please click the play icon on the center of movies below.

| Part.1 Part.2 Movie production: Web Magazine Colla:J SHIONO Tetsuya |

|

Since the opening of the gallery in 1995, Toki-no-Wasuremono has held a Q Ei exhibition essentially every year in hopes of spreading the recognition of his name and works. Last year, we were honored to hold his very first solo exhibition outside of Japan (our 28th Q Ei Exhibition) at Art Basel Hong Kong.

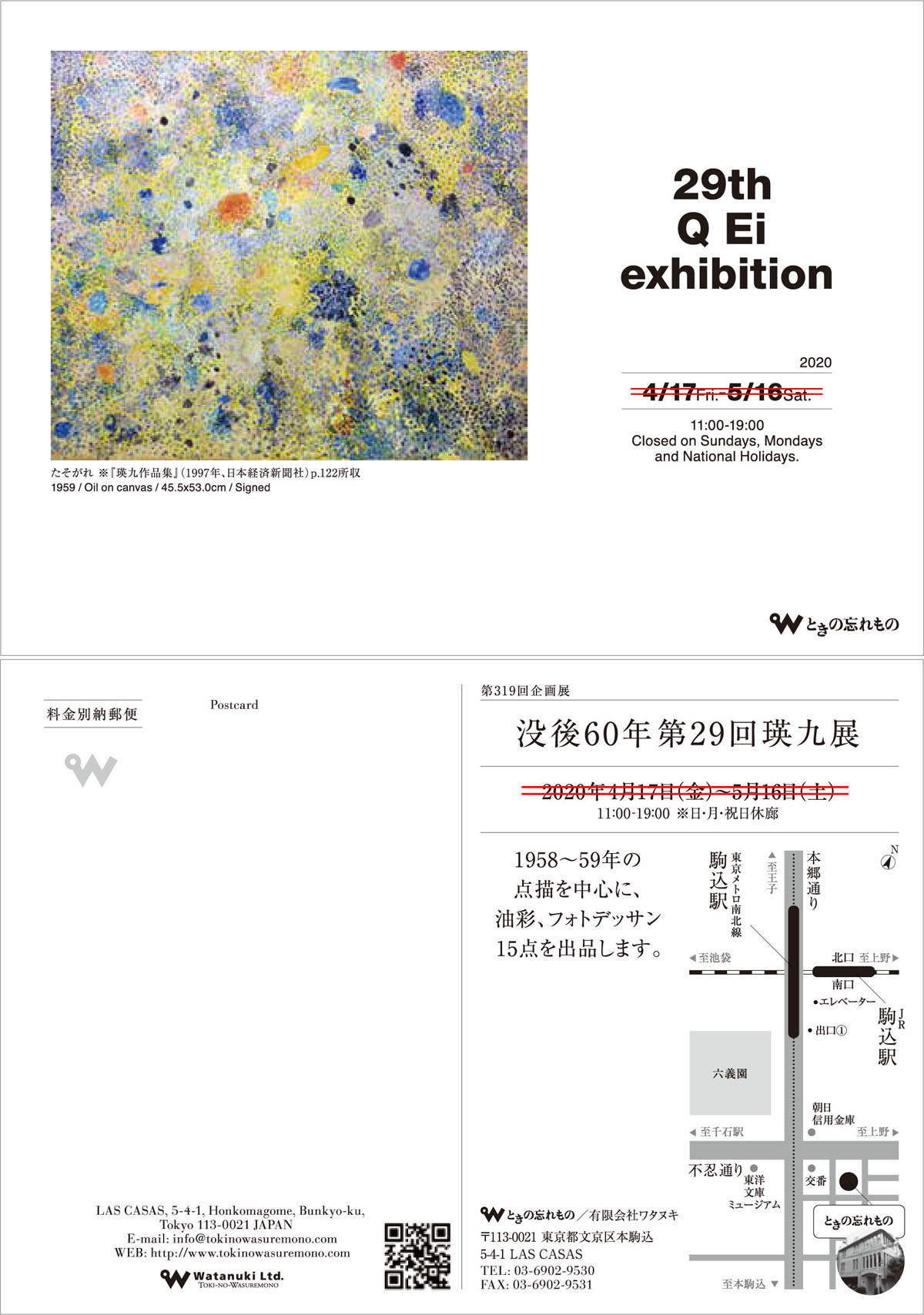

This year, we are holding "60 Year Post-Mortem - 29th Q Ei Exhibition" to commemorate the 60th year after Q Ei's death.

Due to the spreading of COVID-19 and the declaration of a state of emergency, the exhibition has been postponed from April to May, and we will also host it on a web. We will display 15 pieces including oils and photo dessin, focusing on pointillist works from 1958-1959. We have uploaded exhibition scenes on YouTube for viewers to enjoy at home.

If you wish to see the exhibition at the gallery, please reserve an appointment at least a day before your visit.

■ Q Ei(1911-1960)

Q Ei, whose early work was done under his real name of Hideo Sugita, was born in Miyazaki Prefecture in 1911. At age 15, his criticism started appearing in the art magazines "Atelier" and "Mizue". Q Ei’s first collection of photo-dessins, was published in 1936 as "The Reason for Sleep" (Nemuri No Riyu). In 1937, he set up the art organization "Free Art Association" (Jiyu Bijutsu Kyokai). As to criticize the established public group and Japan art world, he set up "Democratic Artists Association" in 1951.

Q Ei had great influence among the young Japanese artists at that time such as Ay-O, Masuo IKEDA, Yukihisa ISOBE, On KAWARA, and Eikoh HOSOE. He challenged various medium such as oil paintings, photo-dessins, prints, and created a unique world of art. He died in 1960 at the age of 48.

Viewing Q Ei’s Late Pointillist Works Online

Otani Shogo (Chief Curator, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

This year, 2020, marks the 60th anniversary of Q Ei’s death. His late pointillist works, "Flow (B)" (1958), "Dance of Red (tent.)" (1958), "Tasogare (Dusk)" (1959), were brought together for this commemorative exhibition, which, with the escalating threat of COVID-19, has been moved online. Although it’s a shame to lose the face to face opportunity, perhaps we can take advantage of this opportunity to focus on the experience of viewing works through a computer screen. When considering Q Ei’s work, such an approach surely has some meaning.

Between 1957 and 59, Q Ei expanded his art style from abstract gatherings of small circular shapes to increasingly minute, sensitive pointillism – the fruits of this development were shown at a solo exhibition at Kabutoya Gallery in 1960 (2/23-28). Of this exhibition, Ogawa Masataka wrote the following review:

“Q Ei is holding his first solo exhibition in 6 years. The 9 works from 1958 and beyond range from size 60 (130x97cm) to 200 (259x182cm). In fact, only 2 of the works are smaller than size 100 (162x130cm). Q Ei has been on bedrest since November of last year, but his adamant desire to hold an exhibition as soon as he could, with the help of his friends, made this show possible.

Q Ei is a pioneer of Japan’s avant-garde art, but his work is not well known – perhaps because he never peacocked across the stage of the art world. But when seeing these pieces, I can’t help but feel that the heft of this period of work was a major pillar in the building of this artist who so concretely dedicated himself to his pursuits. Regarding the style, you could say it might belong to a certain art informel trend, but his yellows, blues, greens, oranges… the image borne from these detailed dots of color is a result of precise calculations of compositions of order and color.

It’s precisely the opposite of the impulsive, intuitive work which characterizes art informel. Q Ei calmly manipulates dots of color to create fresh and fantastic spaces full of movement. His work is unique. “Denen (Pastoral)” which inspires the presence of nature, “Flow – Dawn” with its holy light and space. I would call it a splendid effort” (1).

What is interesting about this review is Ogawa’s comparison of Q Ei’s pointillism to art informel. This movement, slowly introduced to Japan from the beginning of the 1950s, gathered major attention after 1956’s Exposition Internationale de l’Art Actuel. Michel Tapie, the art critic considered a major maker of the movement, visited Japan in 1957, triggering a frenzy which was even called the “informel whirlwind”. While the word itself, informel, can mean irregular, undefined, shapeless, a particularly important influence the movement had on Japanese artists, as Kato Mizuho puts forward, was a shift in orientation to a focus on action and material (2). In this regard, Ogawa’s review is correct. Q Ei’s pointillist works are certainly of “undefined shape” in style, but one could easily say of them, “their essence is in fact quite the opposite of the usual impulsive, straightforward style of art informel”. The question now turns to the nature of this “essence”.

Seo Noriaki classified the development of Q Ei’s late pointillist works into the following 5 patterns (3).

1. Works of concentric circles formed by the nesting of small and large circles

2. Works which have “fireworks”, or slightly larger circles which seem to emit sparks, the jagged rings which surround them

3. Works entirely covered by tightly packed pebble-like color circles

4. Works including dynamic movement which seems to pop to the outer edges from a vanishing point painted by lingering brush strokes

5. His final images featuring fine, minute dots

If we were to categorize the works from the current exhibition, “Dance of Red” would fit into category 2, “Flow (B)” into a combination of 1 and 3, and “Tasogare (Dusk)” into 5. If we pay attention to the way the paint was applied, we can see that as the works go from the 1st to 5th category, the application of the paint gradually thins, its materiality reducing, with the purity of the visual elements growing stronger.

What I’d like to take into consideration now are the abstract photo-dessins which he created at the same time as his pointillist oils. Umezu Gen notes that Q Ei’s interest was spread among various mediums but ultimately remained consistent; in terms of photo-dessin, though the brushstrokes and splashes of pigment were painted all over the glass and cellophane that became the base plate, it would ultimately all be transferred by light onto a piece of photo paper (4). In other words, in regards to his pointillist oil paintings, just like his photo-dessin, the artist’s interest was not necessarily in the emphasis of the paint’s materiality, but rather, targeted at the very image itself.

If that is the case, it makes me want to think that viewing Q Ei’s pointillist oil paintings through a computer screen is actually a rather effective way to enjoy them. On a computer screen, the materiality of the paint itself approaches zero. And the image reaches our retinas through rays of light emitted from the LCD screen.

Of course, I must hasten to remind that in Q Ei’s day, this manner of viewing was hardly an option – his own ideal viewing method was something completely different. Kimizu Ikuo, a collector from Fukui and a supporter of Q Ei, made the following statement. In the summer of 1958, when Kimizu first received the pointillist piece “Mahiru (Midday)” from Q Ei, he couldn’t understand its true value. “It was a fine day. I took the painting out to the yard and looked at it in the sunlight. And there, what did I see? – the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile. It was dynamically reflecting that fierce sense of life from the sunlight of that precise moment. What pride – what presence – I remember how my insides trembled so,” he said. The next year, “in November, I learned of Q Ei’s hospitalization and went to his bedside in Urawa. He lay there in his bed and said, ‘I’ve finished some large works, so I want you to take them out into the yard to see.’ We brought the works from his atelier out into the yard and looked at them like he told us to. -The way we each put in a reservation for one of those large works should be testament to the utter astonishment of those of us who had glimpsed Q Ei’s cosmos” (5).

As relayed in Kimizu’s testimony, it seems that Q Ei wanted his work seen in direct sunlight. That is, as the sunlight reflects off of the surface of the paint and reaches our eyes, the unique quality of the oil paint comes to life. Since Q Ei’s late pointillist works are done in an extremely thin “glaze”, the underlayer of paint appears almost translucent. Under the dazzling sun, the underlayer stands out even more. The juxtaposition and layering of different color dots activates the viewers eye vision so that, as per Kimizu’s recollection, “the black I was so concerned about glittered a silver gray, Q Ei’s blues, his yellows, and reds in concert became so vividly brilliant and mobile”.

This kind of effect cannot be experienced through a computer screen. Neither can “taking them into the yard to see”, the physical experience circling around the works themselves. Regarding the aforementioned problem of “the essence of Q Ei’s pointillism” - if, so to speak, the purpose is for the viewer to encounter the things of this earth bathing under the light of the brilliant sun, and in that act of vision become one with them, and therein experience the joy of life - then it must be said that viewing these works on a computer screen may not in fact provide their complete “essence”. Even so, Q Ei himself wrote regarding the motive for his photo-dessins, “What I’m seeking is a pictorial expression of the mechanisms created in the confusion of the 20th century machine […] The manmade lights and shadows that come together so rapidly among the streetlamps at night are flowers that have bloomed in our machine culture, and so our own vision of beauty must become that sort of sensation as well” (6). Were he alive today, he would surely hold interest in our new forms of seeing. When we encounter online exhibitions, we can ponder that vision as it melds with the image of light that Q Ei sought all his life. And when the threat of COVID-19 finally parts, we can enjoy his works at close range once more.

Reference

1. “An In-Depth Q Ei Solo Exhibition.” Asahi Shimbun, Feb. 28, 1960, p.7

2. Kato Mizuho, “The Reception of Art Informel in Japan”, Sogetsu and Its Era 1945-1970 , Exhibition Catalogue, Sogetsu and Its Era Exhibition Committee, Oct. 1998, pp.88-98

3. Seo Noriaki, “A Bugless Afternoon – Q Ei’s Pointillist Work”, Q Ei The Avant-garde Artists Big Adventure, Exhibition Catalogue, The Shoto Museum of Art, Aug. 2004, pp. 8-9

4. Umezu Gen “Matiere and Gesture”, Fossilization: Imprinted Light Ei-kyu and Photogram Images, Exhibition Catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Jun. 1997, p.114

5. Kimizu Ikuo, “I Like Q Ei”, Q Ei, Father of Contemporary Art, Exhibition Catalogue, Odakyu Grand Gallery, Jun. 1979

6. Q Ei, “On My Works”, Q Ei Photo-Dessin, Exhibition Catalogue, Sankakudo (Osaka), Nishimura Music Store (Miyazaki), Jun. 1936

Gallery view *Click on images to enlarge.

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |